Psychotropic medications are medicines that are used to treat mental health problems such as depression and bipolar disorder. They are commonly used globally, and their use is increasing. People of a child-bearing age are not exempt from needing these medications and sometimes require them during pregnancy (Martin, 2024). Due to safety concerns, pregnant women are rarely enrolled in randomised controlled trials (RCTs), even though evidence generated from RCTs can be interpreted as causal (if performed correctly). This means that the evidence we have for the safety of medications during pregnancy comes almost exclusively from observational studies. Although these types of studies are often larger than RCTs and thus more suitable to identify rare risks associated with medication use, they might be biased by characteristics that differ between the exposed group and the unexposed comparator group.

The evidence that we have to understand the risks that might be associated with psychotropic medication use during pregnancy is inconsistent, with some studies suggesting an increased risk of adverse outcomes (covered by the Mental Elf: Tomlin, 2011; Newhouse, 2014; Fluharty, 2015; Wallace, 2016; Jones, 2016). Others speculate that the illness for which the medication is used might be driving the observed effects.

This umbrella review pooled the results from systematic reviews and meta-analyses that had included individual studies looking into psychotropic medications during pregnancy and potential risks.

Use of mental health-related medications is required in over 1 in 10 pregnancies but evidence for their safety remains inconsistent.

Methods

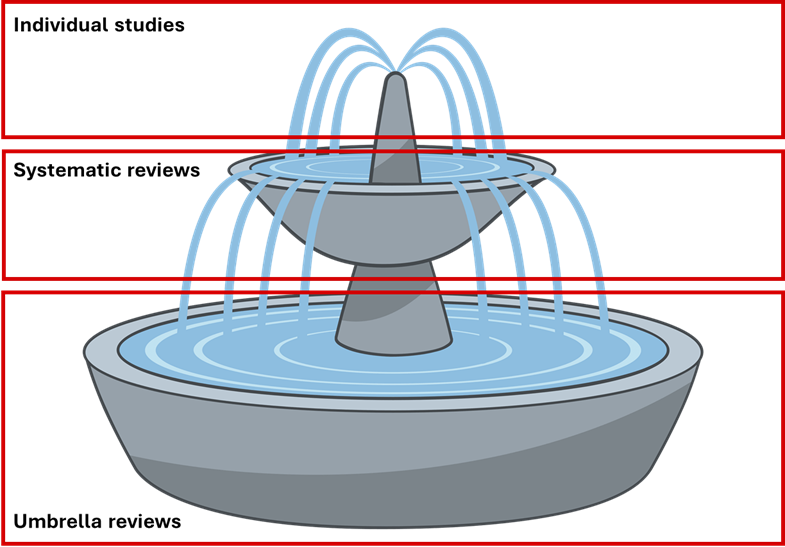

An umbrella review is like a systematic review, but instead of pooling results from individual studies, it pools pooled results from systematic reviews and meta-analyses (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Diagram of how individual studies feed into systematic reviews, and how systematic reviews feed into umbrella reviews.

The authors of this umbrella review searched PubMed, Scopus, and PsychINFO and included eligible systematic reviews that had pooled studies investigating psychotropic medication use during pregnancy and any adverse health outcome (in either pregnant person or baby) as of May 2023. Search terms can be found on their pre-published protocol on Open Science Framework.

The authors used equivalent odds ratios (eOR) to compare relative risks between studies and used the AMSTAR 2 tool, specific to systematic reviews of non-RCTs, to assess the quality of included studies, for example whether included reviews assessed the risk of bias in each individual study.

They also investigated the strength of the associations reported in each included systematic review and graded them as either convincing, highly suggestive, suggestive, or weak evidence.

Results

Following an extensive search of various databases, authors identified 2,748 potential systematic reviews for inclusion in the umbrella review. They excluded 2,486 at the title and abstract screening stage and 241 at the full-text review stage, leaving 21 eligible for inclusion. The 21 included studies were published between 2013 and 2022, and encompassed 17,290,755 participants and 242 individual estimates across 66 individual meta-analyses.

In terms of quality assessment, the authors deemed most included studies were low or critically low quality as per the AMSTAR 2 criteria.

In terms of the strength of the associations reported in the included systematic reviews, none of the studies reported associations that were convincing or highly suggestive, with 68% of the associations showing no evidence at all.

However, this umbrella review did identify some associations based on suggestive or weak evidence:

- Antidepressant use among those with any mental disorder or depression specifically was associated with preterm birth (eOR 1.62, 95% CI 1.24 to 2.12 and eOR 1.65, 95% CI 1.34 to 2.02, respectively).

- Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) use during pregnancy among those with depression was associated with small for gestational age (eOR 1.50, 95% CI 1.19 to 1.90).

- Paroxetine use during trimester one among those with depression or anxiety was associated with birth defects overall, specifically heart defects (eOR 1.24, 95% CI 1.09 to 1.40 and eOR 1.28, 95% CI 1.11 to 1.47, respectively).

- First trimester lithium use among those with bipolar was associated with heart defects and birth defects overall (eOR 1.88, 95% CI 1.26 to 2.81 and eOR 1.97, 95% CI 1.38 to 2.79, respectively), similarly to use any time during pregnancy (eOR 1.84, 95% CI 1.21 to 2.78 and eOR 1.94, 95% CI 1.19 to 3.17, respectively).

- Lithium use for bipolar any time during pregnancy was also associated with preterm birth (eOR 1.91, 95% CI 1.01 to 3.63).

- There was weak evidence to support an association between antipsychotic use during pregnancy among those with any mental disorder and neuromotor deficits, in other words problems with muscle tone and movement.

- The authors did not identify any evidence to support an association between benzodiazepines or opioid maintenance therapy with any adverse health outcomes.

Antidepressant use during pregnancy was shown to be associated with preterm delivery, though none of the included systematic reviews reported associations that were convincing or highly suggestive.

Conclusions

The associations between psychotropic medication use during pregnancy and adverse outcomes were supported by a small number of meta-analyses that provided suggestive evidence at best. The authors concluded that the findings of note consisted of antidepressant use (for any indication) during pregnancy and preterm delivery, SSRIs (for depression) during pregnancy and small for gestational age, and paroxetine (for depression or anxiety) during trimester one and malformations (both any major and cardiac). These data may be used to inform alternative indications for the above medications that do not have their own supporting, indication-specific evidence for safety during pregnancy. In other words, the findings for antidepressant use during pregnancy among people with depression, might be extrapolated to inform potential risks of antidepressant use during pregnancy among people with anxiety.

Antidepressants during pregnancy are associated with preterm delivery, SSRIs during pregnancy are associated with small gestational age, and first trimester paroxetine use is associated with major malformations, although evidence is suggestive at best.

Strengths and limitations

This umbrella review is the first of its kind, assessing psychotropic medication use during pregnancy and adverse outcomes in both the pregnant person and the baby. Not only did the authors pool evidence from several meta-analyses, but they graded the quality of the evidence using well-established criteria and ensured confounding by indication (whereby underlying illness, like depression, that may cause the medication use and the adverse outcome) was accounted for.

As discussed in the introduction, RCTs are rarely performed for pregnant population-level research and were thus omitted from the umbrella review. These types of studies are the gold standard for assessing causality, so the inclusion of only observational studies hinders our ability to interpret the above results as causal.

Although confounding by indication was accounted for, severity of indication was not, as none of the included studies were able to assess this on an individual level. This is an important barrier to the field in general as severity of indication is likely a significant consideration when discontinuing psychotropic medication during pregnancy and is likely associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes.

Although the aim of this umbrella review was to assess adverse maternal and fetal outcomes, only one included study focused on the health of the pregnant person. The authors standardised summary effect estimates (odds ratios, relative risks, standardised mean differences) from individual systematic reviews into an equivalent odds ratio (eOR) to allow estimate pooling in the umbrella review. The eOR did not however include summary hazard ratios from time-to-event analyses.

Unfortunately, the majority of included meta-analyses were deemed low quality by the AMSTAR 2 assessment and the prevalence of each outcome was often not reflective of the prevalence in the underlying population.

Pregnant women are rarely involved in RCTs which limits the conclusions that can be reliable drawn about causal links between psychotropic use in pregnancy and outcomes in the mother or infant.

Implications for practice

It is estimated that upwards of 15% of pregnant people struggle with mental health difficulties and a similar number are on psychotropic medication (Marcus et al., 2004; Andersson et al., 2003). People who fall into one or both categories are vulnerable during pregnancy, where they risk their condition worsening due to pregnancy and/or discontinuation of medication if they choose to stop for fear of fetal effects.

Those prescribed antidepressants who are pregnant or planning pregnancy will benefit from the pooled evidence that antidepressants have been shown to be associated with preterm delivery, small gestational age (SSRIs specifically), and major malformations (paroxetine in first trimester specifically). These findings can assist with evidence-based decision-making in pregnancy prescribing and will facilitate an individualised benefit-risk analysis. Do the modest increases in risk of any of these adverse outcomes outweigh the risk of relapse? People need this type of information to make an informed choice about their care going into or during pregnancy.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) changed their guidance in November 2023 from an indication-severity based set of guidelines to advising a case-by-case assessment of pregnant people on antidepressants. The previous guidelines likely still underpin current clinical practice of assessing patients on their medication regimen, mental health history, priorities, and concerns. The evidence summarised in this umbrella review will provide a useful tool for clinicians to navigate the current literature landscape to best inform and support patients who are pregnant and taking psychotropic medication. It clearly lays out the observed associations and the caveats that must be considered when interpreting the results.

The results from this umbrella review will support evidence-based decision making for those going into pregnancy on psychotropic medication.

Statement of interests

I am a final year Wellcome Trust-funded PhD student whose project focuses on the potential fetal effects of antidepressant use during pregnancy.

Links

Primary paper

Fabiano, N., Wong, S., Gupta, A. et al. Safety of psychotropic medications in pregnancy: an umbrella review. Mol Psychiatry (2024).

Other references

Andersson L, Sundström-Poromaa I, Bixo M, et al. Point prevalence of psychiatric disorders during the second trimester of pregnancy: a population-based study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003 Jul;189(1):148-54.

Fluharty, M. Antidepressants during pregnancy and risk of persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn. The Mental Elf. 2 Jul 2015.

Jones, I. Does taking antidepressants during pregnancy harm the child? Here are the facts. The Mental Elf, 18 Oct 2016.

Marcus SM, Flynn HA, Blow FC, et al. Depressive Symptoms among Pregnant Women Screened in Obstetrics Settings. Journal of Women’s Health 2004.

Martin FZ, Sharp GC, Easey KE, et al. Patterns of antidepressant prescribing in and around pregnancy: a descriptive analysis in the UK Clinical Practice Research Datalink. medRxiv pre-print 2024

Newhouse, N. Antidepressants for depression in pregnancy: new systematic review says the jury’s still out. The Mental Elf, 17 Oct 2014.

Tomlin A. SSRI antidepressants increase the risk of major abnormalities in pregnancy. The Mental Elf, 1 Jul 2011.

Wallace J. Psychotropic medication in pregnancy: new evidence may help achieve a safe balance. The Mental Elf, 17 May 2016.